Git Architecture

18 Nov 2014 • Leave CommentsThree Components

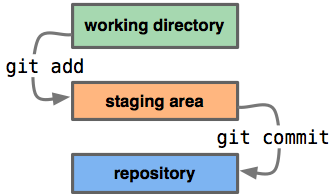

Basically three components:

-

working/local space/directory

The files we edit on hard disk.

-

stage/index area

Temperary place that holds updates from working space and _commit_s the updates to repository.

-

commit history

Besides local repositories, we also have remote repositories.

-

index and repository reside under the .git/ directory.

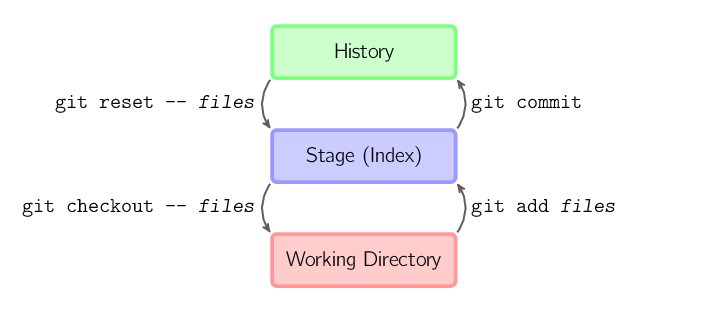

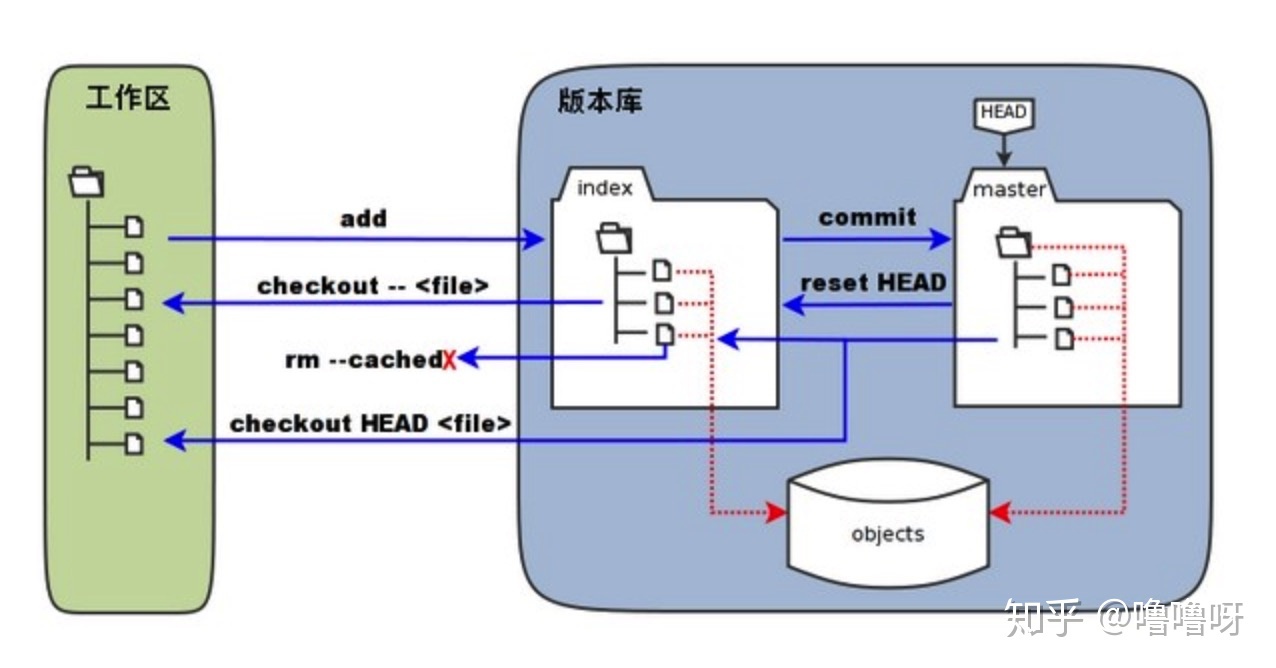

The four commands above copy files between the working directory, the stage, and the history:

git addcopies files (at their current state) to the stage area. We call it a staging process.git commitsaves a snapshot of the stage area to the history. We call it a committing process.-

git reset -- filesunstages files; that is, it copies files from the history to the stage area, namely reset the stage to the preceding state.Use this command to "undo" a

git add. You can also usegit resetalone to unstage everything. It does not affect the working directory or the history. We call it a unstaging process. git checkout -- filescopies files from the stage area to the working directory. Use this to throw away local changes.- We can add

-poption to these commands to interactively choose which files to operate on.

git add can not only add files that are not yet known to Git, but files that we have just created. Git takes contents for next commit NOT from the working directory, but from a special temporary area, called index. This allows finer control over what is going to be committed. We can exclude even certain pieces of files from commit (try git add -i), which helps developers stick to atomic commits principle.

It is also possible to skip the index and updates files directly between the working directory and history.

-

git commit -ais equivalent to running git add on all filenames that already exist in the latest commit, and then running git commit. However, new files we have not told Git about are not affected.git commit <files>does the same thing but only affect files specified on the command line. -

git checkout HEAD -- <files>copies files from the latest commit to both the stage and the working directory. Attention please, there is the HEAD ref.

Here is a brief summary of the commands mentioned above:

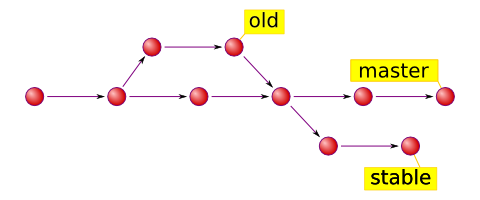

The figure below will be used as a start point of the following sections.

ref

How do we know what is the current state of things? What was the latest commit in the history? To answer that let's look at ref (short for reference) to commits like tag, head (branch), and remote.

Tag is a fixed reference that marks a specific point in commit history, for example "v2.6.29". On the contrary, head always moves forward to reflect the lastest commit. When it comes to commit history, we use term 'head' more than 'branch'. But when we emphasize a module of the project, we use 'branch' more often. Read How do I create tag with certain commits and push it to origin? for detailed difference between tag and head. Whenever we git fetch, it asks the remote repository, what heads and tags does it have, downloads missing objects (if any) and stores under .git/refs/remotes. The remote heads are displayed if we run git branch -r.

For the sake of simplicity, let's forget about tree and blob now, and look at commits illustration:

There are three named head_s above, namely _old, master, and stable representing the latest commits of the three branch_es respectively. Just open _.git/refs/heads directory to inspect heads.

But to know what is happening right here, right now? There is a special reference 'HEAD' (uppercase). Normally HEAD links to one of the heads as current head and does not refer to commit directly unless it is told to do so. HEAD serves two major purposes:

-

It tells Git which commit to take files from when we

checkout.When we run

git checkout <ref>, it makes HEAD point to the ref and extracts files from it. -

It tells Git where to store new commits.

Let's look at a repo with three commits with one tag ("v2.0") and one head ('master'):

HEAD (ref to master)

|

v

a<---b<---c master (ref to commit 'c')

^

|

tag 'v2.0' (ref to commit 'b')

When Git creates a new commit 'd' whose parent is commit 'c', and then updates branch 'master' to point to commit 'd'. HEAD still links to 'master':

$ edit; git add; git commit

HEAD (ref to master)

|

v

a<---b---c<---d master (ref to commit 'd')

^

|

tag 'v2.0' (ref to commit 'b')

It is sometimes useful to be able to checkout a commit that is not at the tip of any named head, or even to create a new commit that is not referenced by any named head. Let's look at what happens when we checkout commit 'b' (here we show three ways this may be done):

$ git checkout v2.0

# -or-

$ git checkout master^^

# -or-

$ git checkout master~2

# -or-

$ git checkout <hash-of-b>

HEAD (ref to commit 'b')

|

v

a<---b<---c<---d master (ref to commit 'd')

^

|

tag 'v2.0' (ref to commit 'b')

Notice that regardless of which checkout command we use, HEAD now refers directly to commit 'b'. This is known as being in detached HEAD state (more details below). This simply means that HEAD refers to a specific commit, as opposed to referring to a named head. Let's see what happens when we create a commit 'e':

$ <edit>; git add; git commit

HEAD (ref to commit 'e')

|

v

e

|

v

a<---b<---c<---d master (ref to commit 'd')

^

|

tag 'v2.0' (ref to commit 'b')

HEAD points to commit 'e' now. We can add yet another commit in this state:

$ <edit>; git add; git commit

HEAD (ref to commit 'f')

|

v

e<---f

|

v

a<---b<---c<---d master (ref to commit 'd')

^

|

tag 'v2.0' (ref to commit 'b')

But, let's look at what happens when we then checkout master:

$ git checkout master

e<---f HEAD (ref to master)

| |

v v

a<---b<---c<---d master (ref to commit 'd')

^

|

tag 'v2.0' (ref to commit 'b')

It is important to realize that at this point nothing refers to commit 'f' and it becomes orphaned commits. Eventually commit 'f' and 'e' would be deleted by Git garbage collection process. To preserve the commits, we can create a ref to commit 'f' before checking out 'master':

~ $ git checkout -b foo <1>

~ $ git branch foo <2>

~ $ git tag foo <3>

- Creates a new branch 'foo', which refers to commit 'f', and then make HEAD link to branch 'foo'. In other words, we'll no longer be in detached HEAD state after this command.

- Similarly, creates a new branch 'foo', but leaves HEAD detached.

- Like above, creates a new tag 'foo', leaving HEAD detached.

Even after we have moved away from commit 'f' without a ref, we can still create a head for it. We must first find out the object name (typically by using git reflog). For example, to see the last two commits to which HEAD referred, we can use either of these commands:

$ git reflog -2 HEAD

# -or-

$ git log -g --abbrev-commit --pretty=oneline -2 HEAD

Remember that heads are dynamic refs that move along with new commits. git reflog or git log can show the moving path.

Git Commands

diff

There are various ways to look at differences between commits. Below are some common examples. Any of these commands can optionally take extra filename arguments that limit the differences to the named files.

Generally, git diff shows changes between working directory and staging area, unless a commit is present.

commit

When you commit, git creates a new commit object using the files from the index and sets the parent to the current commit. It then points the current branch (namely the HEAD) to this new commit. In the image below, the current branch is 'master'. Before the command was created, 'master' points to 'ed489'. Afterwards, a new commit, 'f0cec', and then the 'master' ref moved to the new commit.

Pay attention to the index arrow. Here is another example, a commit occurs on branch 'maint', which was an ancestor of 'master', resulting in '1800b'. Afterwards, 'maint' is no longer an ancestor of 'master'. To join the two histories, a git merge or git rebase will help.

Sometimes a mistake is made when committing, but it is easy to rectify with git commit --amend. When you use this command, git creates a new commit with the same parent as the current commit (would be discarded by garbage collection).

A fourth case is committing with a detached HEAD, as explained later.

checkout

The checkout command is used to copy files from the history or the index to the working directory, and to optionally switch branches.

When a commit given, it updates both the working directory and the index from the history. For example, git checkout HEAD~ foo.c copies 'foo.c' from the 'HEAD~' commit (the parent of the current commit) to the working directory, and also stages it. If no commit name is given, files are copied from the stage to working directory, without any involvement of the history part.

Whichever mode is invoked, that the history is left untouched.

When a filename is not given but the reference is a branch, HEAD is linked to that branch (that is, we switch to that branch), and then the index and working directory are set to match that branch. Any file that exists in commit 'a47c3' is copied; any file that exists in commit 'ed489' but not in the new one is deleted; and any file that exists in neither is ignored.

When a filename is not given and the reference is not a (local) branch (a tag, a remote branch, a SHA-1 ID, or something like 'master~3'), we get an anonymous branch, resulting detached HEAD. This is useful for jumping around the history.

However, committing works slightly different for a detached HEAD, discussed next.

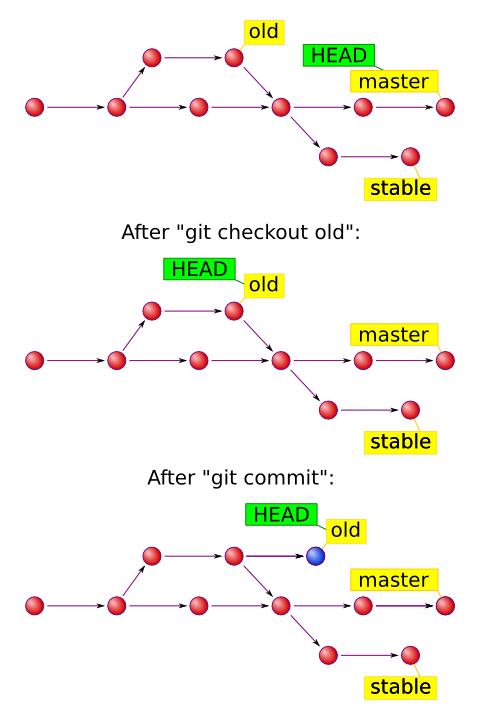

Committing with a Detached HEAD

When HEAD is detached, commits work like normal, except no head ref (think of this as an anonymous branch).

Once you check out something else, say master, the commit is (presumably) no longer referenced by anything else, and gets lost. Note that after the command, there is nothing referencing 2eecb.

If, on the other hand, you want to save this state, you can create a new named branch using git checkout -b name.

This is already discussed earlier in this post.

reset

The reset command modifies the history by moving the current branch to another position. It is updates the stage from history accordingly.

If a commit is given with no filenames, the current branch is moved to that commit, and then the stage is updated to match this commit. If --hard is given, the working directory is also updated. If --soft is given, neither the stage nor the working directory is updated.

If a commit is not given, it defaults to HEAD. In this case, the branch is not moved, but the stage (and optionally the working directory, if --hard is given) is reset to the contents of the last commit.

If a filenames (and/or -p) is given, only that file is reset.

merge

A merge creates a new commit that incorporates changes from another branch into the current branch. Before merging, the stage must match the current commit. A trivial case is if the other commit is an ancestor of the current commit, in which case nothing is done.

Another simple scenario is if the current commit is an ancestor of the other commit, the ref is simply moved forward and the other commit is checked out. This results in a fast-forward merge.

Otherwise, Git would replay all commits until the head of the other branch. Take the following figure for example, it basically takes the current commit 'ed489', the other commit '33104', and their common ancestor 'b325c', and performs a three-way merge. A new commit 'f8bc5' is created with two parents, namely '33104' and 'ed489'. The result is saved to the the stage and working directory.

cherry-pick

The cherry-pick command applies patches of existing commits to the current branch with the while preserving the message.

It is more of a simplified version of 'merge'.

rebase

Rebase is similar to merge but operates on branch level. A merge creates a single commit with two parents, leaving a non-linear history, whereas a rebase replays the commits of the current branch onto another, and move the current head there, leaving a linear history. In essence, this is an automated way of performing several cherry-picks in a row.

The figure below takes all the commits that exist in 'topic' but not in 'master', replays them onto 'master' and then updates 'topic' to the new tip. Note that the old commits will be garbage collected if they are no longer referenced.

To limit how far back to go, use the --onto option. The following command replays onto master the most recent commits on the current 'topic' since '169a6' (exclusive).

There is also the --interactive option, which allows one to do more complicated things than simply replaying commits, namely dropping, reordering, modifying, and squashing commits. There is no obvious picture to draw for this; see "git-rebase(1)" for more details.

.git/ directory

There are three kinds of '.git/objects':

- blob for file

- tree for directory

- commit.

All objects are compressed in binary format, but Git provides git cat-file -t|-p|-s command to examine objects.

The '.git/index' file lists filenames along with the identifier of the associated blob, as well as some other data.

Commit objects have an additional data type, a tree, identified by SHA-1 hash too. Trees correspond to directories in the working directory, and contain a list of trees and blobs corresponding to each filename within that directory. Each commit stores the identifier of its top-level tree, which in turn contains all of the blobs and other trees associated with that commit.

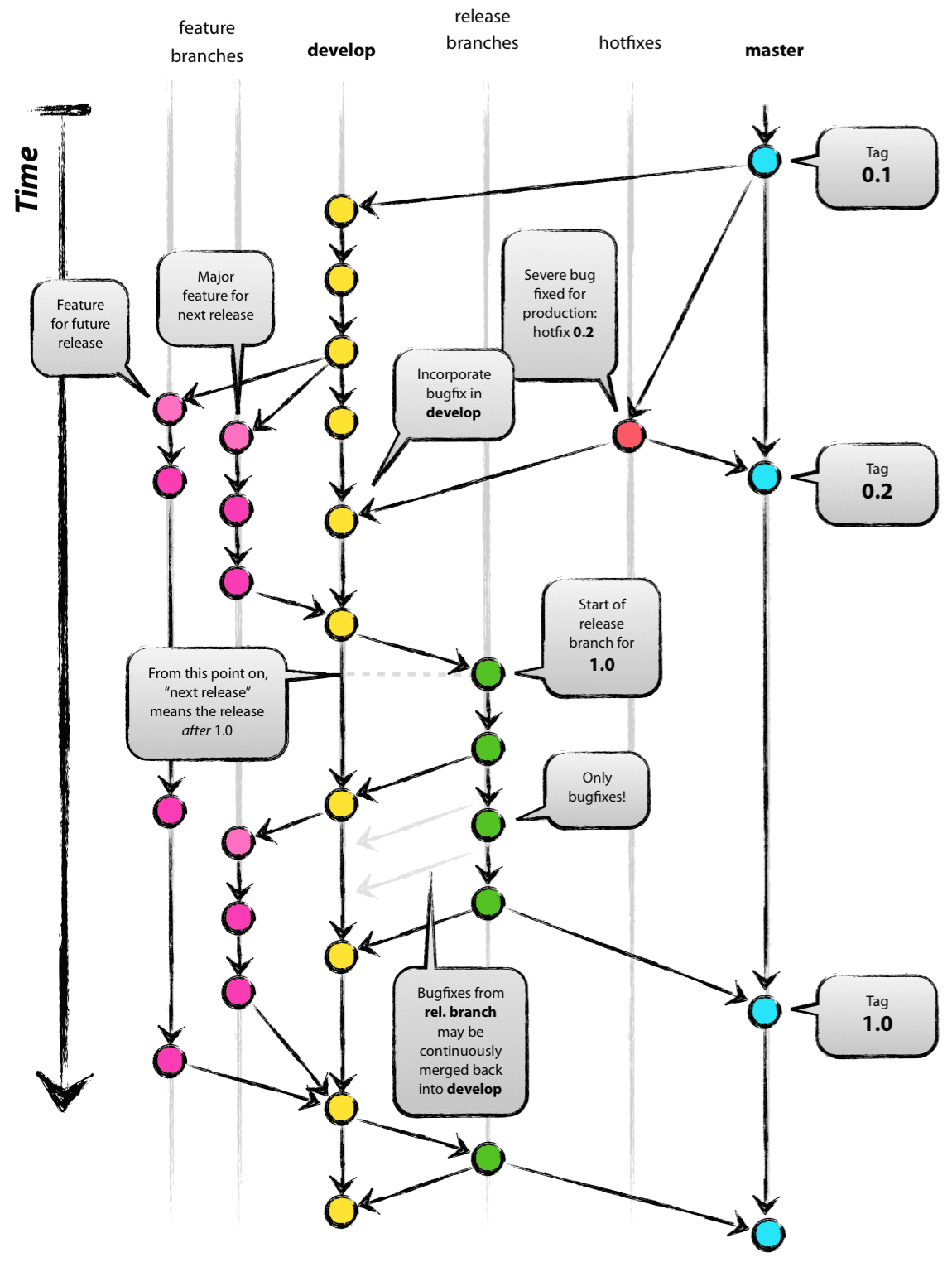

A successful Git branching model